Nearly all healthcare clinicians have or will encounter ethical dilemmas during their clinical practices. Consequently, majority them will not get training on how to make sense and ultimately solve the situation. Ethical dilemmas may affect the psychological decisions one makes since one may anticipate the fear of going beyond the limits of what is morally, socially, or even legally acceptable. According to an article, an ethical dilemma involves the need to choose between two or more morally acceptable options or between equally unacceptable courses of action, when one choice prevents the selection of the other (Ong, Yee & Lee, 2012). Due to the continuous growing and advances in medicine, increasing and unpredictable economic stress, rise in self-determination amongst patients and the many different cultural, gender and beliefs amongst healthcare clinicians and patients, are all factors which contribute to the complexity of ethical issues and dilemmas. Furthermore, because of different standards, guidelines and rules ethical dilemmas may often arise in clinical practices.

Allen (2012) states that: “There are three conditions that must be present for a situation to be considered an ethical dilemma The first condition occurs in situations when an individual must make a decision about which course of action is best. The second condition for ethical dilemma is that there must be different courses of action to choose from. Third, in an ethical dilemma, no matter what course of action is taken, some ethical principle is compromised. In other words, there is no perfect solution”

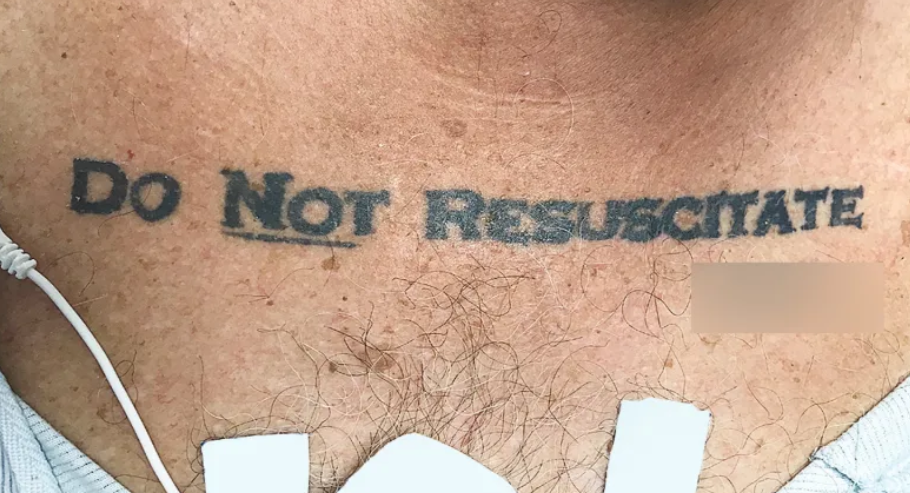

I came across an ethical dilemma when I heard about Mr P. He is a 72-year-old man (at the end stage of colon cancer) who was in a motor vehicle accident. He sustained life-threatening injuries; he was also in a coma, which lead him to be mechanically ventilated. In the early morning hours, the doctor on duty had already performed Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) on him twice. CPR is an emergency procedure, which is performed on patients when they go into cardiac arrest in efforts to maintain life, rebuild health, and prevent disability (Ong, Yee & Lee, 2012). According to a blog written on Livestrong, CPR has many complications such as broken bones, internal injuries, vomiting, aspiration, body fluid exposure and gastric distension. Unfortunately, those complications may limit the patient’s chance to make a full recovery (Otto, n.d.). More risks include a decrease level of consciousness and a chronic coma, leaving the patient in a vegetative state, which is worse than death or a costly, long time stay in the ICU after CPR. Mr P became a widower when his wife died 5 years ago. His children lives abroad and the medical team could not yet come in contact with them. During ward rounds, one of the doctors spoke about that the patient had a living will drawn up, but that there were no specifics. In other words, Mr P stated that he wanted a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order once he was in a vegetative state and that there was no longer a chance to full recovery. Some of the healthcare clinicians felt that he still has a chance to make a full recovery with the needed medical interventions, while others felt that this will not honour the patient’s wishes and may lead to a vegetative state.

The debate started when one of the doctors asked: “If Mr P’s heart stops beating, should CPR be initiated?”

The ethical principles such as autonomy and non mal-efficiency, should always be taking into account when during ethical decision-making. One article notes that it is not morally acceptable to prolong a person’s life at all costs without taking into consideration to the quality or the potential threats and burdens of the treatment (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016). Moreover, there is a fine line when it comes to balancing the risks and the benefits of treatment and this should apply and be taking into account to use any form of medical intervention, including CPR. Unfortunately, elderly patients who have been diagnosed with chronic illnesses have survival rate of less than 5% and for those with advanced illness have a survival rate less than 1% (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016). Therefore, when looking in Mr P’s case, he has an extremely low survival rate.

In addition, an ethical dilemma may arise when Mr P stated in his living will that DNR should not be carried out, however he does not give any specifications. Therefore, the healthcare clinicians are faced with the decision the either carry out the wishes of Mr P or to make a decision based on what is legally correct.

In terms of legal opponents, many studies show that there is a higher mortality rate among patients, whom has the DNR label. Furthermore, the study concludes that the death rate was noticeably higher among these patients (Ayoub, 2013). Many authors feel that although there are personal, relational and philosophical considerations with patients deciding on the DNR code, there is however a gap in the matter of fully understanding the DNR utilization process. Therefore, the healthcare clinicians play a vital role in ensuring that this critical issue is discussed in a clean, concise and precise manner to guarantee that the patient is fully orientated and fully understand this process. Legal implications such as falsification of rules which is put into place to control social conduct in a formal and legally binding manner. In countries such as China and South Korea, it is unlawful to great legal approval to withhold CPR. In addition, the British Medical Association feels that people who are have the DNR code may have been neglected and not receiving the benefits of being treated fairly in response to no CPR, in contrast when a competent and fully aware younger patient is refusing CPR (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016).

On the other hand, authors; Ong, Yee and Lee (2013) stated that recently there have been an increased amount DNR codes among hospitals, which shows increasing survival rates among those who undergo CPR. In Jordan, there is a policy approved by the Medical Board, which enables patients to refuse CPR efforts. In addition, this concept of DNR is reinforced legally in the Patient Self Determination Act of 1991, which specifies that hospitals should respect the adult patient’s right to make an advanced care directive (living will) which clarifies their wishes for end of life care (Ayoub, 2013). The American Heart Association acknowledges that CPR is not indicated for all patients and that when an individual with an irreversible and a terminal illness, in many cases where death the is expected outcome, does not generally benefit from CPR (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016). Another consensus made from the American Nurse Association and the American Society of Anaesthesiology to support the patients’ right to self-determination. This right included that by law the component and fully alert patient can refuse life-saving procedures, taking into account that they fully understand and are fully aware of the implications of their decision and allow natural death without CPR efforts. The conclusion was made that in the case of healthcare clinicians who attempt to resuscitate patients against their wishes, they are violating the patients’ human rights to self-determination. The Americans view the DNR code as a legal medical document which reflects the patients’ decision and desire to avoid life prolonging interventions (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016).

In terms of ethical opponents, one article states that the patient does not possess the full and accurate mental capabilities to make an informed decision. Moreover, autonomy is affected by anxiety and depression (Ayoub, 2012). When a patient is comatosed, it is unacceptable to have the DNR code as it may be seen as injustice and unfair to take the decision on their behalf. In this case, justice is defined as equally distributing benefits, costs and risks; suggesting that patients in similar positions and situations should be treated in a similar manner (Ayoub, 2012). Taking this into consideration, people who have the DNR code will then not receive the benefits and being treated equally and they might even be neglected or under-treated in this case. One of the factors which shape our moral and ethical codes are religion. According to the Quran and Sunni, it is believed that the human soul is respected. Similarly, this is also believed amongst Christians. As a result, many people who disagree with the DNR code rely fully on what their religion says and this forms the basis of their moral and ethical codes. Another article states that it’s commonly felt that the moral approach is to try a new medical intervention, in the case of when a patient’s heart nearly stops beating (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016).

However, a study done by Ayoub (2013) shows that when DNR orders are integrated into the health care system, it will lead to two major benefits, namely; equipping patients with the right to self-determination and autonomy and also, that there will be no negative side effects from CPR, since it will not be used. Although end of life decisions by the DNR are difficult decisions, the ethical approach simplifies the complexities and facilitates shared decision-making. Furthermore, the CPR guidelines should take into account the ethical principles and not just the technical and legal issues, which the patient faces. Moreover, taking incorporating the considerations of the patients in order to respect the patient’s autonomy, avoiding any harm or additional suffering can surely be justified into giving the patient equal opportunities. The healthcare clinicians detain a better medical understanding and clinical reasoning; therefore sometimes the decision to not attempt CPR is made out of a clear medical perspective. If the healthcare clinicians believe that CPR will fail in a certain patient’s care, then it should not be started. The healthcare clinicians then makes a decision based on their training, skills and knowledge to provide the best intervention possible (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016).

The DNR code may definitely lead to an ethical dilemma, when looking at the numerous opposing and proposing views. It is important to note that in some cases, CPR, interventions to continue the end of life, may have adverse effects on patients, and some suffering may appear worse than death. In this patient’s case, although Mr P’s family is oversees, it is still almost intolerable to know that one’s father is suffering. Another thing to take into consideration, the DNR code does not mean that the patient will pass away alone or uncared for, the healthcare clinicians will ensure that the patient is comfortable and in as little pain as possible. In addition, CPR may is less beneficial when the patient’s quality of life is so poor that no meaningful survival is expected. As mentioned earlier, the DNR code continues to remain a difficult concept, in spite of healthcare clinicians’ efforts to aid the families and patients to make informed decisions (Sa’id & Mrayyan, 2016).

To conclude, in difficult situations where life and death is involved, prompt decision making should take into consideration that although the family may be hurt or the healthcare clinicians do not agree with the decision, it is the patient’s own decision. As a physiotherapy student, it is important for me to be as neutral as possible and to remember that it is a personal decision taken by the patient. For some patients living with chronic, irreversible illnesses, death may offer an end to the suffering. Healthcare clinicians should adopt incorporate a collaborative approach when it comes to discussing the end of life decisions, such as the DNR code. This collaborative approach should include seeking the views of the patient, the family members (only when the patient is unable to make a clear decision) and the multidisciplinary team involved with the patient.

References:

Ayoub, A. (2013). Do Not Resuscitate: An Argumentative Essay. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2258603

Allen, K.N. (2012). The new social worker. Spring 2012, Vol. 19, No. 2.

Ong, W., Yee, C., Lee, A. (2012). Ethical dilemmas in the care of cancer patients near the end of life. Singapore medical journal, vol. 53, issue 1, pp. 11-6

Otto, E. (n.d.). Livestrong. Retrieved from https://www.livestrong.com/article/31439-complications-cpr/

Sa’id, A.N., Mrayyan, M. (2016). Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine, 6:2. DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000254

2 thoughts on “Do Not Resuscitate: the ethical dilemma”

Hi Jana

I enjoyed reading your piece ever tho it is a longer one. I like how you used your reference and clinical experience to make the writing piece more relatable. Just remember to put a DNR in () the first time next to the meaning.

Paragraph 2 : mechianically-mechanically

During ward rounds, one of the doctors spoke about, that the patient had a living will drawn up, but that there were no specifics.

“If Mr P’s heart stops breathing(beating), should CPR be initiated?”

Paragraph 6: refinforced-reinforced

in many cases where death the is(is the) expected outcome

includeds-includes

Paragraph 7: depression

similar(2)

Some sentences is very long and has a lot of information in, maybe you can break the sentences up to make it easier to read.

Hi Jana

Thank you for your submission! This is such an excellent and interesting topic to discuss.

You have done a fantastic job at looking into every point of view, and using evidence to back up each statement. I really like how you related the topic so well to your experience in clinical practice. More so, it was very clever to related the entire piece back to physiotherapy and how it effects you are a therapist.

One correction, in the 5th paragraph, you accidentally said NDR, instead of DNR.

Well done!!! This was an excellent and enjoyable read, thank you!

Sonali xx