Once you’ve made a decision about the problem you’re interested in investigating and have a basic understanding of the work that has currently been done in the domain (via your preliminary literature review), it’s important to start thinking about the specific paradigm that will contextualise your study.

What this means is that you need to think about what kinds of data you need to gather that will allow you to answer your research question. Understanding the kind of data you need will inform the methods you use to gather that data. In order to better understand research design, you should first be familiar with the concept of a research paradigm:

A paradigm can be defined as a “set of interrelated assumptions about the social world which provides a philosophical and conceptual framework for the organized study of that world” (Filstead, 1979).

Paradigms (or, ways of thinking about the world) offer varying beliefs about what can be known and how it can be known. This means that paradigms determine the types of research questions that are asked, the research approach taken, and ultimately, the data collection and methods of interpretation that are used (Wright et al., 2016). It is essential to recognise the alignment between our beliefs about what it is possible to know, how we can come to know it, what approach should be used, and what specific tools are apprpriate for data gathering and analysis (ibid.).

Subjective (interpretive) paradigm | qualitative data

The interpretive position assumes that there are multiple, apprehendable, and equally valid realities that are constructed in the mind of the individual, rather than it being an externally singular entity (Ponterotto, 2005). Research conducted within the interpretive paradigm begins from the premise that some information is not quantifiable. Or rather, that reducing the variable of interest to a number is too reductionist and that something important is lost when we do this. For example, asking a participant to rate their emotional response to a traumatic event is problematic because the subjectivity of the rating isn’t possible to account for. In other words, we have no way of knowing if my “Very angry” feels the same as someone else’s “Somewhat angry”. The inability to generalise subjective responses across the sample makes it problematic to gather quantitative data in order to address the research problem.

Qualitative methods refer to a broad category of procedures that are used to describe and interpret the experiences of research participants within a specific context or setting. These findings are usually presented in everyday language and incorporate participants’ own words to describe an event, experience, or phenomenon (Ponterotto, 2005). These methods are often used to generate a theory or explanation of some phenomenon by using inductive reasoning that starts with data and uses it to generate an explanation, theory or description. This is usually localised to a specific context and cannot be generalised to other groups (Wright, et al., 2016).

Objective (positivist) paradigm | quantitative data

The positivist paradigm focuses on efforts to verify a priori hypotheses that are usually stated in quantitative propositions that can then be converted into mathematical formulas that express relationships between variables. The primary goal of positivistic inquiry is an explanation that can be used to predict and control phenomena. Research conducted within this paradigm assumes that there is an objective reality that exists outside of the personal experiences, values and beliefs of both the researcher and the research participants. It takes for granted that some values can be reduced to quantitative values and that statistics can be used to determine the relationships between these values. For example, it is possible to say with certainty that some percentage of smokers are at an increased risk of developing lung cancer at some point in their lives. The relative risk is quantifiable with statistical modeling, even though it is impossible to say anything with certainty about the likelihood of an individual developing lung cancer.

Quantitative methods used to gather data focus on the quantification of data, in association with control of the variables that influence the data. It usually makes use of sampling at large scales and the use of statistics to establish either causal or correlational relationships between variables (Ponterotto, 2005). These approaches usually test a theory about how something works in the world using deductive methods that start with a theory about a phenomenon and conclude with data points that confirm or disconfirm the theory (Wright, et al., 2016). The findings are usually generalisable to other populations besides the study sample.

A research design spanning these two paradigms is that of mixed methods. When a study uses mixed methods to answer a question, the researcher is usually attempting to take advantage of the strengths of one approach to make up for the weaknesses of another. Sometimes the idea is to use qualitative data to try and explain findings obtained via quantative data. For example, you conduct a survey that gathers information via scales and then conduct interviews among some respondents in order to better understand why they answered in certain ways. Alternatively, you may conduct a series of focus group interviews and then ask participants to fill out a survey in an attempt to better understand the dynamics observed in the group.

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches are empirical methods that involve the collection, analysis, and interpretation of observations or data. It is also important to note that, while positivist (objective reality, quantatitive data) and interpretive (subjective reality, qualitative data) are common paradigms used in research, there are others e.g. postpositivist and critical. Postposivitists accept that there is an objective reality but that we can only ever understand it imperfectly. The critical paradigm aims to challenge the status quo and the research within this approach specifically aims to transform and emancipate participants (Ponterotto, 2005). In later sections of the course we will describe in more detail different methods of data collection, analysis and establishing trust in the different paradigms.

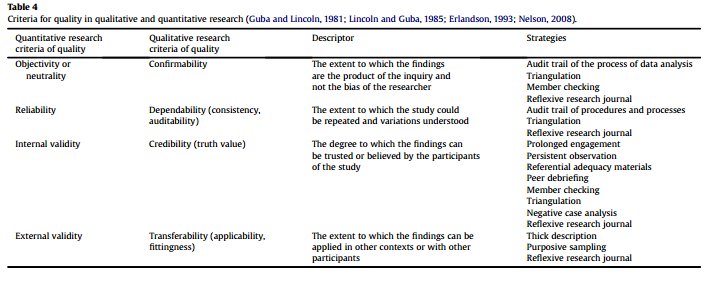

Here is a helpful table that provides examples of the different ways of describing approaches in the two main research paradigms.

It is unreasonable to suggest that any single paradigm is “better” than any other, since they are each valid ways to think about how we understand the world. However, it is very important to make sure that the methods used to gather data are appropriate to the paradigm in which the study is being conducted. If the research problem under investigation can only be answered with statistical modeling, then it makes no sense to interview participants to find out what they think or believe about it. Likewise, if your aim is to explore participants emotional response to traumatic events, a 5 item Likert scale is unlikely to produce valid outcomes.

You must be clear about the paradigm in which your topic is contextualised so that you can more clearly make decisions about what methods to use to gather data. You will also then have a much better idea about why you are doing certain things. It’s no good saying that you want to do a survey and that you’ll use open- and close-ended questions. A good understanding of research paradigms will do a lot to ensure that your study is well designed.

References and resources

- Filstead, W. J. (1979). Qualitative methods: A needed perspective in evaluation research. In T. D. Cook & C. S. Reichardt (Eds.), Qualitative and quantitative methods in evaluation research (pp. 33–48). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Greenhalgh, T. (1997). How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ: British Medical Journal.

- Greenhalgh, T. (1997). How to read a paper: Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ: British Medical Journal.

- Greenhalgh, T. (1997). How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ: British Medical Journal.

- Greenhalgh, T. (1997). How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal.

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 320(7226), 50–52. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136.

- Tai, J., & Ajjawi, R. (2016). Undertaking and reporting qualitative research. Clinical Teacher, 13(3), 175–182.

- Wright, S., O’Brien, B. C., Nimmon, L., Law, M., & Mylopoulos, M. (2016). Research Design Considerations. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 8(1), 97–98.